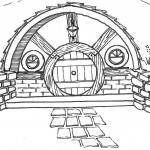

“In a hole in the ground, there lived a Hobbit…”

With these words J.R.R. Tolkien launched an epic fantasy that has thrilled generations of readers. Yet he chose to begin his story with not with action nor with characters, directly, but with setting. Why?

Because in some stories, such as this one, setting is so vitally important to the story that it becomes almost an invisible character in its own right. The story simply could not happen apart from the setting. Let’s look at three examples:

In The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins (and indeed, every Hobbit by nature) is excessively fond of home as a symbol of comfort, security and permanence. In a figurative sense, you might almost say that Hobbits “bury their heads in the ground.” The troubles that happen in other places do not much concern the residents of the Shire. They imagine that troubles only happen in other places. Hobbits love the predictability of each season and are generally content as long as meals are served on time. They value a life of peace in community with others. It is crucial to Tolkien’s story that we understand these things from the outset so that we grasp how very reluctant Bilbo is to take part in any adventure, what motivates him to become a “burglar”, and how desperately he longs to return home–only to realize that he never really can. The setting in this story is a symbol of the character’s motivation.

In The Hobbit, Bilbo Baggins (and indeed, every Hobbit by nature) is excessively fond of home as a symbol of comfort, security and permanence. In a figurative sense, you might almost say that Hobbits “bury their heads in the ground.” The troubles that happen in other places do not much concern the residents of the Shire. They imagine that troubles only happen in other places. Hobbits love the predictability of each season and are generally content as long as meals are served on time. They value a life of peace in community with others. It is crucial to Tolkien’s story that we understand these things from the outset so that we grasp how very reluctant Bilbo is to take part in any adventure, what motivates him to become a “burglar”, and how desperately he longs to return home–only to realize that he never really can. The setting in this story is a symbol of the character’s motivation.

In J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, we find another example of a vital setting–Neverland, a place where childhood is carefree and endless. To understand why Neverland is critical to the story, we need to understand a bit about the author. J. M. Barrie had an older brother who died in an ice skating accident the day before his 14th birthday. He would “never grow up,” and his grieving mother never recovered the loss. She spent her days in bed in a darkened room. When Barrie went on occasion to visit her there, she, like Wendy, would ask, “Is that you, boy?” and Barrie would answer, “No, Mother. It’s only me.” Could it be that Neverland represents the author’s wish that children who die prematurely are able to enjoy a happy eternity in a place where they never grow up? When Peter Pan eavesdrops at barred windows, listening to childhood stories, might that be the author’s way of saying it’s important never to forget lost children? Or might he, himself, be looking back to the happy family life he enjoyed before the accident? There are many theories, but it seems clear that in this story setting is a symbol of the author’s motivation.

Finally there are stories such as Alfred Lansing’s Endurance, the astonishing biographical account of explorer Ernest Shackleton’s survival for over a year on the ice-bound Antarctic seas. In this story the setting is the “villain”–the obstacle to be overcome, and so Lansing describes it in detail.

Finally there are stories such as Alfred Lansing’s Endurance, the astonishing biographical account of explorer Ernest Shackleton’s survival for over a year on the ice-bound Antarctic seas. In this story the setting is the “villain”–the obstacle to be overcome, and so Lansing describes it in detail.

The more essential setting is to your story, the more time you can spend describing it to your reader. (Conversely, if setting is NOT critical to your story, a long, flowery description will seem pointless and boring to most readers.) We’ll take a look next week at specific tools you can use to make your setting come alive!

Exercise:

- Identify the setting in books you are currently reading.

- Could the story have happened in some other place, or is the setting vital to the story?

- How much time did the author spend describing the setting?

- What sensory elements were used to make the setting come alive to readers?

Speak Your Mind

You must be logged in to post a comment.